The State of Vermont was mapped in extraordinary detail 150 years

ago. Between 1854-1859 mapmakers from Philadelphia and Boston descended

upon this rural area and made the first complete road maps.[1]

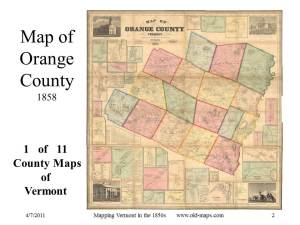

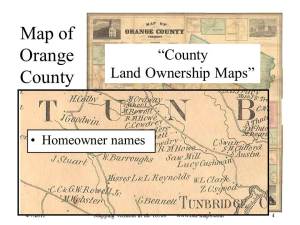

The results of their work were eleven large wall maps. Not only were

all the roads mapped for the first time, but these maps showed the names

and locations of all homes, churches, schools and businesses.

These

old maps are a remarkable snapshot of a moment in time in Vermont’s

history. No maps today are made with the sort of detail these 19th

century mapmakers made for us. Today the 1850s maps help us learn who

lived in our houses in centuries past or whose house once set upon an

old foundation far off into the woods.

And

of course these maps are a huge resource for genealogists because of

the names – 1000s of names attached to the house locations. I estimate

between three and five thousand names are on each of Vermont’s 11 large

county wall maps.

These were commercial maps – made by business men from Boston and Philadelphia. The Vermont maps were just part of a wave of similar maps made of most of the United States and all of the populated northeast. Though my subject is Vermont, the material generally applies to the other New England states. All of NH, Mass and CT were mapped in the same manner in the same decade.

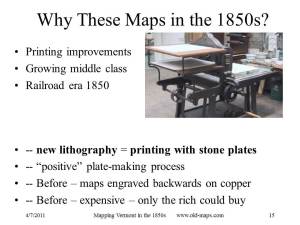

Changes in printing technology, a

growing middle class, and railroad transportation preceded the county

map boom in America. The mechanics of printing was especially

important. Prior to the mid 1800s, printed maps were rarely made of

local areas such as towns or counties. Map making was expensive, and

you typically needed a broader subject like an entire ountryo generate

enough sales to make a profitable venture. Maps were engraved in reverse

on metal plates by hand. This was a laborious process, and could only

be done by skilled craftsmen.

About

1850 lithography, printing on large limestone plates, became widely

available along with a positive transfer process which allowed the map

to be drawn in its final form. This and other changes made short-run

printing of maps much less expensive.

The

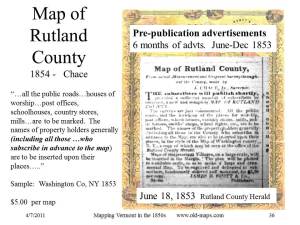

first Vermont county map was of Rutland County, published in 1854 by

Jacob Chace Jr. and James Scott of Philadelphia. These men had just

issued a county map of nearby Washington County New York which they

showed in Rutland. The surveys, conducted by Chace, began in June of

1853. We

know this because advertising started on June 18 in the Rutland

newspaper and continued for six months. Mapmaking was expensive so 19th

century mapmakers took advance orders, often while they did the

surveys. The surveyor used a compass to record angles and a wheeled

odometer for distances. The odometer and compass and the surveyor who

carried them were an unusual sight in rural Vermont, a fact which no

doubt helped the sales efforts. The surveyor would ask th e name of each

homeowner and tell him that the map would feature his name and his

house, and wouldn’t he like to buy a copy. The price was five dollars, a

considerable amount of money at the time. Publication was announced a

year after the project started. “It is a large…and very accurate map…”

announced the Rutland County Herald on June 9th, 1854. That

claim notwithstanding, the Rutland County 1854 map is in fact among the

least accurate of the Vermont county wall maps. Chace and Scott were not

the best mapmakers publishing in Vermont in the 1850s. More on accuracy

later.

e name of each

homeowner and tell him that the map would feature his name and his

house, and wouldn’t he like to buy a copy. The price was five dollars, a

considerable amount of money at the time. Publication was announced a

year after the project started. “It is a large…and very accurate map…”

announced the Rutland County Herald on June 9th, 1854. That

claim notwithstanding, the Rutland County 1854 map is in fact among the

least accurate of the Vermont county wall maps. Chace and Scott were not

the best mapmakers publishing in Vermont in the 1850s. More on accuracy

later.

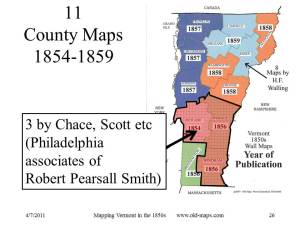

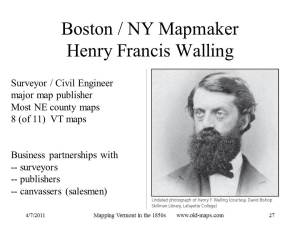

There were two major figures in 1850s county map

publishing, Robert Pearsall Smith and Henry Francis Walling. The most

prolific was Smith, a Philadelphian who printed over 300 county maps

with dozens of surveyors and publishers, including Chace and Scott.

The other was Henry F. Walling of Boston (and later New York), a

professional engineer who produced dozens of New England town maps and

about fifty county wall maps. His training and inclination led to the

publication of maps which are generally more accurate than those made in

Philadelphia. Three Vermont county maps were made by associates of

Smith and eight were made by Walling. There was tension between the

competing mapmakers. For example, Walling intended to map Windsor

County but was pre-empted by Smith who copyrighted his county map

(surveyed by Hosea Doton) in April, 1856. Walling had announced his map

in the fall of 1854 with a paid advertisement describing the quality of

his work and warning that “parties from Philadelphia are …publishing

county maps from mere eye-sketches…entitled to no confidence…” The

problem for Walling may have been that his maps took more time to

produce – he never issued a Windsor County map. The timetable for

Walling’s 1858 Caledonia County map is instructive. It too was

announced in late 1854 (with a warning about the Philadelphians). The

final map was copyrighted in August 1858 almost four years later. His

Chittenden County map took about two and a half years, still longer than

the Philadelphia mapmakers’ single year. Walling's reference to “mere

eye sketches” was a way to contrast the surveying methods used by the

competing mapmakers. Walling is known to have used proper surveying

techniques with careful measurements of angles and distances and

adjusting the various road survey loops to remove as many errors as

possible. A less careful mapmaker would not bother the tedious

adjustments, and would do some of his mapping by skipping the compass

and odometer work if he could see the roads stretching out before him –

using "eye-sketches" - which was possible in 1850s Vermont.

The other was Henry F. Walling of Boston (and later New York), a

professional engineer who produced dozens of New England town maps and

about fifty county wall maps. His training and inclination led to the

publication of maps which are generally more accurate than those made in

Philadelphia. Three Vermont county maps were made by associates of

Smith and eight were made by Walling. There was tension between the

competing mapmakers. For example, Walling intended to map Windsor

County but was pre-empted by Smith who copyrighted his county map

(surveyed by Hosea Doton) in April, 1856. Walling had announced his map

in the fall of 1854 with a paid advertisement describing the quality of

his work and warning that “parties from Philadelphia are …publishing

county maps from mere eye-sketches…entitled to no confidence…” The

problem for Walling may have been that his maps took more time to

produce – he never issued a Windsor County map. The timetable for

Walling’s 1858 Caledonia County map is instructive. It too was

announced in late 1854 (with a warning about the Philadelphians). The

final map was copyrighted in August 1858 almost four years later. His

Chittenden County map took about two and a half years, still longer than

the Philadelphia mapmakers’ single year. Walling's reference to “mere

eye sketches” was a way to contrast the surveying methods used by the

competing mapmakers. Walling is known to have used proper surveying

techniques with careful measurements of angles and distances and

adjusting the various road survey loops to remove as many errors as

possible. A less careful mapmaker would not bother the tedious

adjustments, and would do some of his mapping by skipping the compass

and odometer work if he could see the roads stretching out before him –

using "eye-sketches" - which was possible in 1850s Vermont.

[1] Prior to these wall maps there were a few detailed road maps made for Vermont’s larger town centers, such as Burlington, Rutland, and Brattleboro, but the most of the states roads were unmapped. The federal government's road mapping (topographic maps) did not begin until the end of the 19th century.